Phil Woodhouse

BY PHIL WOODHOUSE

Lyndon Anderson – Skua

Mark Jennings – Rosco Kayaks, Southern Raider & Paddling Perfection, SeaBear

Stu Baker – Penguin Kayaks, ’Torres’

Philip Woodhouse – Mirage 582

As part of a veteran’s adventure rehabilitation program run by Mates Hero Help and Lyndon, we departed Cairns on July 1, 2019 and headed north for Cape York. Lyndon and Mark had done the trip 16-years ago from Cooktown, but this time we all decided that we wanted to see the Far North Queensland (FNQ) coast from Cairns northward to Cooktown. Having said that, Lyndon had run sea-kayaking trips along this section of coast several times before and was familiar with it and its hazards.

From my perspective, the coast in this region is spectacular. The razor-back hills and tropical vegetation come down to the sea, creating an incredible contrast of thick rainforest with mottled rich dark shades of green, which intersect abruptly a shimmering sea, coloured with contrasting blues, greys and turquoise. By the second day we arrived at Wonga Beach, where Mark and I chose to go on a 500-metre portage over and through a rock garden to the beach and set up camp. Lyndon and Stu decided to wait several hours and just let their kayaks float to the beach.

Under the lush palm trees and vegetation at Wonga Beach, Stu swapped out his Penguin Kayaks ’Torres’ for Mark’s SeaBear that we organised to be dropped up at the location by Dave Sterritt, from Townsville. Mark then decided he would like to paddle the Torres, so he swapped his Southern Raider for Stu’s Torres.

Cape Tribulation

Cape Tribulation

The next day we paddled past the Daintree River mouth and then Cape Tribulation. After Cape Tribulation easy access sandy beaches were a premium because, as can be seen on the charts, there is a rock shelf that guards the beaches and exposes at low tides. The rock ledge with the tides we were experiencing, exposed a wall up to 0.6-metres high. Additionally we were faced with long portages once we got onto of the rock shelves. We found a way through the rock shelf maze near Donovan Point, but found the only suitable camping spot backed onto a deep creek. Looking at the only ideal campsite along the beach, we were certain the creek would be home to a salty. Moving on we approached Cowie Beach in the early evening, but could not get past the 200-metre wide rock shelf that was 700-metres from the beach.

We unloaded the camping equipment from the kayaks and walked back and forwards to the beach, setting up camp while waiting for the incoming tide to float the kayaks past the rock shelf to the 500-metres of sand flats. By 6:30 p.m. in the gathering dark, we had enough water to get the kayaks past the obstructions. We put the wheels on and portage the kayaks across the sand flats to the beach and our tents.

Portage at Cowie Beach

North of Cowie Beach, the vegetation changed from lush rainforest to scrubby dry Queensland bush, but it was still a delight to behold from the water. At Archer Point we landed, however a fisherman’s four-wheel drive vehicle caught fire and set the surrounding grasslands and bush on fire. After tracking the fire’s progress we relocated from our preferred campsite to a position where we would not be trapped by the fire. Moving on, we landed at a beautiful beach at Quarantine Bay then rounded the coast and paddled up the Endeavour River to Cooktown. Until this time, during the days the steady state wind was generally SE 10-knots in the morning and rising to SE 15–20-knots in the afternoon. We had some light rain and overcast days but generally by the afternoon it was quite sunny.

At Cooktown we took a day off to repair two of the kayaks, as they needed fibreglass patching. My kayak had been cracked open at the seam-line, where one of the team accidentally rammed his stern into my midships. Mark by this time had enough of paddling the Torres with its quirks, so went back to his SeaBear. He spent sometime trying to find out how water was leaking into his rear hatch and getting past the bulkhead into his day hatch. He also modified the rear deck to secure the kayak wheels to. Lyndon’s 22-year old Skua was the only serviceable one at this stage of the expedition..

After a morning repairing the kayaks, we sorted our provisions and water for the next major stage to Portland Roads. For this second stage, we took vitals for fourteen days. I carried 39-litres of potable water, mostly in MSR Dromedary bags. I used two 10-litre, one six-litre and one four-litre Dromedary bags as well two-litre and one-litre water canisters. I found the six-litre Dromedary bag, fitted nicely behind my rudder pedal bar in the cockpit and did not become dislodged. Mark used multiple two and one litre soft drink bottles for his water.

Before departing Cooktown a Yachty approached me and informed me that it was blowing 20–30 knots out past Cape Bedford, which was 30-kilometres away. After rounding Cape Bedford we got into the lee of the wind; and here I was informed of a route change. Instead of going around to Elim Beach we crossed over to Low Wooded Island in quite boisterous conditions. Unbeknown to me, Lyndon had lost his chart overboard rounding Cape Bedford with the charted route to Low Wooded Island. After Lyndon consulted the Navionics chart, we set out on a compass bearing into the two to three metre seas with no visual navigation references. Having no visual navigational references, we all knew that we would drift to the west of our destination, but we were looking for a navigation feature. Once we found our reference feature, Conical Rock that was 10-kilometres out from the cape, we were able to work out our drift and make a dead-reckoning correction to the destination 7-kilometres away, that was still not visible. By this stage the Mirage 582’s cockpit was a swimming pool due to the cockpit coaming coming away from the deck: so much for Mirage Kayaks motto printed on the deck: “Expedition Proven”!

At this point I should point out how I like to navigate. I prefer a chart and or map on my deck, of the route and a deck compass. I also carry a Silva baseplate compass in my PFD pocket. I do not rely on my GPS as I had a waterproof device that leaked on one of my Bass Strait crossing, rendering it useless. I still carry a GPS for my check-navigation and plot but turn it on as required. I also carry my waterproof GPS in a waterproof clear bag.

On reaching our destination we searched for a route through the coral to the beach to enable us to launch unimpeded the morning. Next morning we broke camp early and launched at first light without breakfast, so we could get past the coral reef. In overcast and strong winds conditions, we crossed over to Cape Flattery and did surf landings on the lee-shore. After breakfast and several attempts, we all got off the beach and headed for the Turtle Group of islands.

By time we had crossed over to the islands the cloud had gone and the wind had become light. We admired this beautiful part of FNQ as we sat on a tropical uninhabited island looking at turquoise blue waters, white sand and palm trees. The only draw back was that you could not go down to the waters edge. That afternoon we repaired the kayak’s hull damage, which they all obtained on the reef of Low Wooded Island.

We continued north and visited Coquet Island and camped on Leggatt Island. The next day while heading to Barrow Point, my bow pearled and picked up a yellow sea snake. After Barrow Island we followed the coast to Hales Beach. Along the way we saw brumbies and wild pigs as well as many Leatherback turtles.

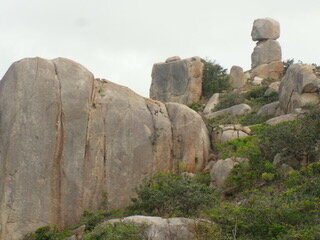

By day-10, we reached the granite features at Cape Melville and the famous H2O sign painted onto the granite boulder. I first saw this sign in a picture in Wild Magazine in the 1990s and had always wanted to go there. After picking up fresh water, we crossed the 25-kilometres of Bathurst Bay to the Flinders Island Group near Bathurst Head.

Cape Melville H2O

This area had abundant marine life as well as a host of biting insects. On Wurrima––Flinders Island––there are two water tanks and a concrete pad covered area with picnic tables and chairs. We spent a day exploring the islands before starting our multi-day island hopping crossing of Princess Charlotte Bay and up to the Chester River. The small islands along this route predominantly had northerly facing sandy spit beaches and crystal clear water over the reefs. At one island, Mark had a shark wanting to be his friend, as it followed directly behind him along his meandering course for quite some distance and time.

On route to Stainer Island we encountered strong cross-currents. The waters here are funnelled by the large reefs––Stuntip, Grub, & Hedge––that lay to seaward. When we got to Stainer Island and its solitary tree, we discovered that we would be extremely close (one to two metres) from the water’s edge when we set up camp, due to the large tide. Pushing on in the late afternoon we approached another Island. As part of our standard operating procedure for landings, we sat off the beach on the water and reconnoitred the beach and surrounds. On this occasion, we counted multiple large crocodile drag marks up and down the sand. “So”, we all thought to ourselves, “where are they?” In the gathering darkness we paddled to the lee-shore, reconnoitred and landed.

Part of our risk management plan (RMP), was to land and get off the water as quickly as possible. We carried a single axel set of wheels with a V-block midway between the wheels. The wheels on this were made of solid soft rubber that did not need inflating. While one person stood watch at the back of the kayaks armed with his trusty paddle, the other two would attach the wheels to the stern. We would all then wheel the kayaks up the beach. Another important part of our risk management plan was, once getting off the water we would not go back to the waters edge. When it came to launching, we always tried to launch away from where we landed, to avoid repetition and getting ambushed by a Salty.

However, in a psychological attempt to help us sleep at night––since we were so unavoidably close to the water’s edge––we harboured the kayaks between the water and the tents and with whatever vegetation was available, to create a ‘noise’ warning barrier. At night when we moved around, we always swept the area we were travelling to with our torches and informed the others of our intentions.

Pelican Island

The next day we continued on to the Chester River region of the coast. When planning we had considered camping on some of the other islands but they were now all surrounded with thick mangroves. Lyndon and Mark were amazed at how much the vegetation had increased around the islands in sixteen years. This meant that the once viable camping options had become high-risk areas through the presence of estuarine crocodiles.

Of note was one island that had a three-metre high steep sloping soft white sand beach, leading to a flat grassy area that was ideal for camping. Unfortunately for us, there were crocodile drag marks present. Crossing to a place north of Chester River, we lost all wind and associated following sea. We sweltered in the humid heat and ground out the strokes to get across to the coast. As we crossed over to the mainland, we admired the Great Dividing Range in the background, with its isolation and hundreds of kilometres of mangroves and waterways in the foreground. To cool down I did think of rolling my kayak, but in the calm warm water, there was the unknown presence of Irukandji and box jellyfish.

We landed well north of Chester River but discovered the beach backed onto mangrove swamps and the sandy beachfront had numerous crocodile tracks. Heading northward we saw kangaroo, cattle, pig and brumby tacks. As for marine life, there were many turtles. We stayed close to the beach, about 30-metres off, as we reconnoitred for a campsite.

Camp at ?Orford Ness

At this stage of the afternoon the wind was cranking up and the waters were turbid. As we paddled along, a three-metre plus salty was traveling toward us, oblivious to our presence. In hindsight our initial reaction was rather amusing. This encounter had been researched, analysed and plan for, as part of our RMP; but when you have no way to defend yourself from a wild creature there is a moment of uncertainty in the possibilities and outcomes of the encounter. As per our RMP, we closed together and when the animal saw us it sank under the choppy turbid water. We calmly paddled on but looking over our shoulders to see if there was any hint of the creature. We joked that each of us, had a two-in-three chance of not being attacked.

The author, Cape Melville area

With the tide dropping, the wind strength increasing and churning up the turbid water, we landed and floated/portage the kayaks above the high water mark. We unloaded the kayaks and walked a further 200-metres across a sandy wind-swept plain to a windbreak afforded by a large clump of bushes. Tragically from here along the coast all the way to Cape York, was an enormous quantity of plastic flotsam and jetsam on every beach.

The next day, the winds drove us towards the beach even though we were set at an acute angle to avoid the beach. As we yawed along the coast, we endeavoured to give the mouth of the Nesbit River as wide a berth as possible. The reason for this was to reduce the possibility of encountering salties.

At Cape Sidmouth my sail’s stub-mast snapped in two. It had been bent by the winds after we left Cooktown but the loads and metal fatigue cause it to fail in the strong winds. After making repairs we set off, but later Mark encountered rudder issues and my sail tore––as a result of the temporary repair. In the vicinity of Voaden Point, we realized the risk management “lemons” were stacking up against us. Lyndon, who was the only one not experiencing failures, decided that we should land early. We reconnoitred the long expanse of plastic littered beach, for a campsite and found shelter from the wind in the bushes. Here we did repairs to broken items and organised ourselves to continue the adventure north.

Our next destination was Cape Direction. With our now usual strong winds and two-metre seas we approached the cape. The winds dropped a bit, but we had enjoyable clapotis around May Rock and the cape. Landing on the weather shore, which was on the northern-side of the cape, we performed our usual back and forth portage routine without second thought. While sitting up on the hill overlooking the beach a very large crocodile surfaced and cruised past. Considering we were 16-kilometres from the Lockhart River, we were not surprised. This cape has amazing wind sculptured rock formations and fresh water in a reentrant between the two sides of the Cape. Just look at the vegetation and you will see the difference if you ever go there.

Next was a 28-kilometre crossing to Restoration Island. This island was named by Captain Bligh and was his first landing after being chased off the ‘Friendly Islands’ after the Fletcher Christian led mutiny. This is an amazing place. After negotiating three-metre standing waves that were created by both the wind and running tide we landed and were warmly welcomed by Peter, who lives on the island. After viewing the sights of the settlement, we went over to Chilli Beach and met up with Stu and Bridgette.

Cape Direction boulders

Because of Stu’s service related injuries he pulled out at Cooktown but then continued on northward to Cape York by road. Here they greeted us with cold beer and rib-eye steaks. We took the next day off and repaired the kayaks. We also picked up our postal packages of food from the Portland Roads Post Office.

After resupplying with ten-days food and water, we set off and passed the WW2 settlement of Portland Roads. We rounded Fair Cape and started looking for a campsite. After 45-minutes of walking up and down the beach we settled back at the spot we first dismissed. By this time the winds were definitely 25-knots and increasing. The sand, whipped up by the wind, grit blasted our bodies and covered our tents, although they were ‘sheltered’ behind the dunes. While trying to find a sheltered spot, Lyndon and I disturbed a Green Ants’ nest in the bushes. After performing the now famed ‘Fair Cape Slap Dance’ we sat down and enjoyed our meals with copious amounts of sand toppings.

Our next leg was a 42-kilometre crossing to Haggerstone Island and Gore Island. On the crossing we entered the Piper Group. This was a magical place with its abundant marine and bird life, turquoise-blue crystal clear waters that magnified the variegated and diverse corals below. Stopping on Farmer Island I was the last one to land.

Lyndon had done the beach reccy and was up on the grasslands that preceded the bushes and trees. Mark was still at the bow of his kayak getting snacks out. After I got out of my kayak and as I was walking through the shallow water up to the bow of my boat, to drag it up on the beach, I felt a powerful thump on my leg and heard the loud sound of a solid object hitting the kayak. In a nano-second my senses heightened and my mind raced as I tried to make sense of what was happening. At my feet, between my kayak and me, was a sandy speckled coloured crocodile. Both Lyndon and Mark also, did not see or hear the animal make its 30-metre dash from the grass, where it was hiding, down to the water. I do not know its length, but its mid-body girth was 35 to 40 centimetres wide. Only after we both departed ways, did I begin to understand what had just happened. The little fellow had come ashore about 40-metres from where we landed, but had moved through the grassland above where Lyndon and Mark came ashore. While Lyndon had walk off up the beach past the reptile, the creature made his dash for the water, but I just happened to be in its direct escape route.

Here is a good place to include our observations about the estuarine (a.k.a. salt-water, salty) crocodile, from this trip. We had all worked in areas inhabited by crocodiles. Before the trip I had done extensive reading and interviews with crocodile handlers. Lyndon had also performed updated research, as part of our risk management plan. A consolidated version of this research can be found in the book Sea Kayaking A Guide for Sea Canoeists.

Croc Watch

In windy choppy conditions, crocodiles see you before you see them. In calm conditions you may only see the eyes and or eyes and nostrils as they watch you. Their skin colour matches the places where they inhabit. The crocodiles around the sandy islands were a sandy speckled brown colour and they blended into the grass patches. Crocodiles around the river mouths and mangrove areas were a darker brown colour. Where there were a lot of turtles, there was always crocodile sign. On Lyndon and Mark’s trip 16–years ago, they only once saw crocodile sign from Cooktown to Cape York and no sightings.

Continuing on with a bruised and scratched leg, we crossed to Haggerstone Island. This island has a private $1300 per day resort. After picking up fresh water and an enormous 1.5 kg lobster tail, we crossed over to Gore Island and looked for a campsite. We had a rest day here as it was an incredible spot and so isolated. I again repaired my ‘expedition proven’ Mirage 582’s faulty coaming but this time I used FixTech Fix2 instead of marine Sikaflex.

Crossing to Haggerstone Island

During the trip, Lyndon had a tube of Sikaflex rupture in his hands and got the sealant everywhere besides the job at hand. What he discovered was ‘wet wipes’ cleans the sealant off of your skin and gelcoat.

The next leg was 63-kilometres to Captain Billy’s Landing. We rounded Cape Grenville and admired the massive sand dunes that shone pure white like snow-covered mountains. I would have like to spend a day or two here exploring but the group decision was to go on. Crossing over to the MacArthur Island Group we had freshening winds and increasing size waves as the fetch increased. Twelve kilometres into the 22-kilometre crossing my right forward metal rudder pedal cable snapped on my ‘expedition proven’ Mirage 582. All this meant was, I lost the ability to trim out my kayak.

On reaching the group, we crossed a large lagoon with plentiful marine life, including many turtles and sharks. While crossing the lagoon, the tide was dropping and we soon banged our kayaks on oyster-covered rocks. Once we cleared the lagoon we landed on a beautiful high sandy island. I dragged my kayak up and replaced the broken cable and inspected the hull damage. Thinking the hull damage was only negligible I was ready to paddle. Lyndon inspected his kayak’s hull and also thought his boats damage was negligible.

A note about Lyndon’s 22-year old, 17-foot Skua. It was designed by Malcolm Cowell and built by Terry Wilmont. It is a heavy fibreglass and gelcoat layup. This type of construction–in my opinion–far out weighs any gains in lightweight construction methods for expedition paddling.

While I was repairing my ‘expedition proven’ Mirage 582, Lyndon explored MacArthur Island and photographed a Salty’s footprint that was bigger than the span of his hand. This is the same island that Arunus Pilka was attacked on 20-years before.

That afternoon we crossed to Captain Billy’s Landing and landed in the late afternoon. The next day we repaired the kayaks, because when we landed the evening before, we noticed how excessively heavy some of the kayaks were. On inspection we all found holes in our kayak’s hulls. The reasons for the damaged resulted from environmental protrusions through to the gel-coat being worn away in the areas where the bulkheads attach to the hull. The wear damage was especially evident in the ‘expedition proven’ Mirage 582’s thin gelcoat. Because of the construction method, the Mirage 582’s hull had numerous delaminations between the fibreglass and the composite woven mat material.

Kayak damage

Once the thin gel-coat cracked, water seeped into the hatch spaces past the delaminated fibreglass and mat materials.

Other items that failed by this stage of the trip were Pelican Boxes. These waterproof containers were used to house the bilge pump batteries for both the Skua and SeaBear. The waterproof containers leaked. As a result the batteries failed thereby rendering their electric bilge pumps useless. To reduce the chance of pump failure, I have my battery in a Plano Guide Series waterproof case, mounted five centimetres off the day hatch floor on the forward bulkhead.

Seaworthy once again, the next day we set off for Ordford Ness. In strong to near gale force winds we had our bows pointing in a northeasterly direction in an attempt to paddle in a northerly direction. As we yawed along the coast, from my diary I note, that we entered into a confused sea and had waves breaking over our heads. Landing at False Ordford Ness we enjoyed the beautiful secluded beach and rainforest that came right down onto the high-water mark. We roamed the cliffs and found running fresh water soaks. Once again I had water in my front hatch! So the hunt went on to find the points of ingress.

We next crossed Orford Bay. During this crossing my repaired and reinforced stub-mast snapped in two. When I was performing “bush repairs” on the stub-mast at Chilli Beach, I noticed a potential failure mode and sure enough it eventuated. We continued for another two hours or more up the coast before landing. At this point in the trip we all knew how to do a quick repair and re-rig the sail and mast. Within 15-minutes we were back under way heading to Sadd Point. Here the once pristine tropic paradise beach was a plastic rubbish dump.

A comment on stub-masts is appropriate at this stage. I was using the standard stub-mast design that enables the mast, with sail attached, to slide on over the stub-mast. The stub-mast has the stays and up/down-haul halyards attached. The mast and sail have the sail’s halyard. Lyndon normally uses a Tasmanian Storm Sail design. This design is simple in that it does not require a stub-mast and its associated rigging. To raise the sail, all the paddler has to do is lean forward and place the mast through the deck at about the area of their feet––depending on how flexible they are. There is only one halyard and that is on the sail. After some pre-expedition sail experimentation, he chose to redesign the stub-mast to be of larger diameter than the mast. Therefore the stub-mast becomes a moveable receptacle for the sail and mast. This proved to be stronger than the regular design and at no stage did he have any issues in the strong winds with his stub-mast. However, after this trip he is going back to the Storm Sail design. Another big advantage of the Storm Sail is that if you capsize it is easier to discard the sail and self-rescue. The regular design is cumbersome to collapse under water and self-rescue; trust me I know! If you choose to use the standard stub-mast design, replace the rivets with bolts and nuts. Also use thick walled aluminium and or reinforce with stainless steel tubing.

On our voyage to Somerset Beach, we passed Turtle Island on the seaward side. At this stage my atrial fibrillation had set in and I struggled to make-way. Landing on Turtle Island for a break I was feeling exhausted. Wanting to be a team player and not hold up the team, I decided to push on. We proceeded to cross the 21-kilometres to Albany Pass assisted by a following sea of two to three metres. On approaching the Pass, we encountered a tidal race. The chart shows the race as having a 4.5-knot current. Surfing two to three metre waves, we made our way into the pass. At times we all estimated that some of the waves were around four-meters high as we surfed down them. Once inside the pass, we admired the scenery and landed at Somerset Bay for the night.

From Somerset Bay we caught the tide and cruised around to Cape York. Without paddling we were travelling at 13.6 km/h.

After taking on-water pictures, we landed in Frangipani Bay and walked up to “The Tip”. One tourist asked Lyndon where he had travelled from. When Lyndon told him, the man simply did not believe him. Paddling the last 28-kilometres to Seisia we had wind-on-tide then no wind. On the last 18-kilometres section, we saw 11 crocodiles. Once again the crocodiles on the rocks blended in. As there was no wind, the ones submerged up to their nostrils and eyes were relatively easy to spot.

At Seisia we calculated that we had travelled by kayak 1028 kilometres in 25-days. It was a brilliant trip with great mates. If it were not for the abundant stock of “snapping-handbags”, I would recommend this trip. At Seisia we later paddled around some of the islands but noticed a lot of crocodile sign and a 2.5-metre to three-metre croc cruising around. The company Sea Swift generously took our kayaks and Lyndon back to Cairns on their regular FNQ shipping run. I visited Thursday Island and Horn Island before flying back to Cairns.

Approaching Cape York

A note on the not-for-profit, Mates Hero Help. The organisation was started by Lyndon Anderson and Michael Sheehan and provides adventure rehabilitation based sea kayaking activities. These activities are open to current serving and ex-Defence Force Personnel, as well as Police and all branches of Emergency Services Personnel. Adventure based rehabilitation actives are designed to positively challenge participants physically and psychologically. These activities are tailored to place the participants in a controlled, safe but foreign to them environment. It has been found that by facing a safe level of physical or psychological stress, and being pushed outside of their comfort zone, participants regain confidence and self-worth. The activities also build motivation, teamwork and trust and provide the participants with a goal to work towards and a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

Three at The Tip, Cape York